Angle of Repose is a 1971 novel by Wallace Stegner (1909-93) which won the Pulitzer Prize for 1972.† Controversy has accompanied this novel over the years, especially after the publication in 1972 by Huntington Library Press of the memoir by Mary Hallock Foote, A Victorian Gentlewoman in the Far West.

Now plagiarism is one thing, and fictionalizing real people’s lives while adapting them to the demands of your narrative is another. It’s a truism that having a novelist in the family is bound to lead to trouble. In 2022 Alta magazine did a piece by Sands Hall entitled Did Wallace Stegner Steal ‘Angle of Repose’ from a Woman?.

I dare say there may be some men whose lives have been used by an author, either as a source of story or labor, without credit and possibly without adequate thanks, but the traditional image has always been of the poor woman slaving away to support the struggling author. For me one major archetype in this regard is New Grub Street‘s Marian Yule, beavering away in the British Museum Reading Room, gathering material and drafting the many articles “written” by her cantankerous father Alfred, who always gets the by-line.

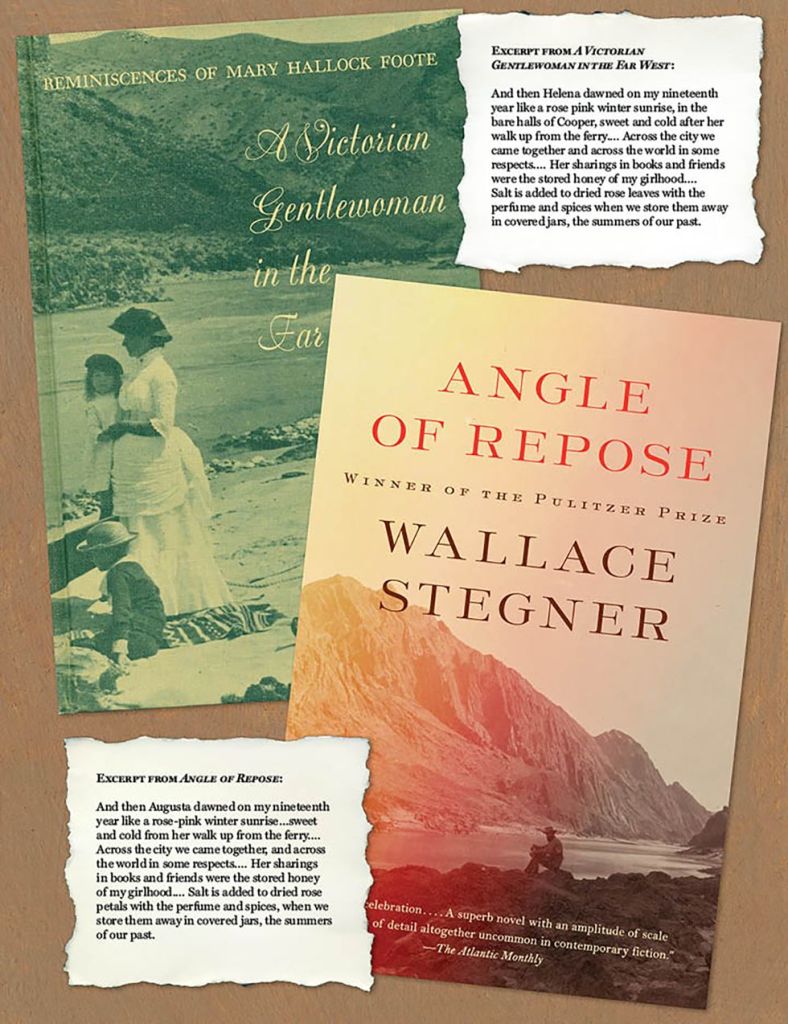

It seems clear that Stegner definitely used the reminiscences of Mary Hallock Foote to create the character Susan Burling Ward, grandmother of the novel’s narrator Lyman — and hence basically the whole story. And Stegner apparently embroidered on her history to hint at an affair. Ms Hall claims that “Scene after scene drawn directly from Reminiscences shows up in Repose, as do many lengthy verbatim quotes”. Maybe scene after scene was reused, but the worst one can really say about that is that it displays perhaps a lack of invention in a novelist. “Many lengthy verbatim quotes” are however a horse of a different color. Unfortunately the only example we are given in Ms Hall’s essay is the case illustrated in this picture from the Alta piece:

For all the potential injustice of silently using the life of a dead person for your fiction, we know this sort of thing happens — how are you to make it real if you don’t make it real. Do the descendants of the original of Wackford Squeers have a beef? I suspect not — but if some modern day Dickens would have been caught quoting from their grandfather’s diary, there would possibly have been be a law case. If there are more direct quotations in Angle of Repose I wish we’d been shown them, because they make the meat of Ms Hall’s accusations.

The New Yorker provides a bit of help. Roxana Robinson tells us that “In 2000, in an introduction to the novel, Jackson Benson, Stegner’s biographer, defended Stegner’s inclusion of thirty-eight passages from Foote’s letters, ‘approximately 61 pages,’ all without attribution. It’s ‘a brilliant tactic,’ Benson says, that creates ‘an invaluable part of the novel’ and provides ‘depth and authenticity’.” Sixty-one pages is quite a lot, even in a 554-page novel, and Ms Foote writes well. There are indeed extensive quotations from letters allegedly written by Granny Ward, but I can’t imagine that a bit of editing hasn’t gone on, if only to fit them to the characters and events of this story. There’s a vagueness about the evidence of plagiarism. Sure, Stegner used a lot of direct quotes from the letters and diary of “Susan Burling Ward”, but what we don’t get to find out from Ms Hall and Ms Robinson is just how much of the Burling text is unaltered Foote text. Storms do of course occur in teapots, but I have to assume that direct quotation is in fact quite extensive. Ms Robinson doesn’t like the book Angle of Repose and claims that Stegner’s writing in places where he adapts Foote is lifeless and plodding, which isn’t calculated to make the critic sympathetic to her author.

The case for the defense, I assume, would rest mainly on the fact that the family of Ms Foote had encouraged Stegner to use their grandmother’s material, but I suppose they may not have been alive to the full implications of their “permission”. At the time Stegner was writing Angle of Repose Foote’s Reminiscences had not been published. Lyman Ward, our narrator is a retired historian, and can be seen using historical materials to build up his account of his grandparents: he quotes a lot. Especially from his “grandmother” Susan Burling Ward (alias Mary Hallock Foote). Just how close this copying is should I guess at the heart of how one regards the charge of plagiarism. Of course, it goes without saying that a more thoroughgoing attribution than the sort of oblique acknowledgment Stegner places at the front of his book would have been preferable. He writes as part of the front matter of the book, on a page of its own, so quite prominent, “My thanks to J.M. and her sister for the loan of their ancestors. Though I have used many details of their lives and characters, I have not hesitated to warp both personalities and events to fictional needs. This is a novel which utilizes selected facts from their real lives. It is in no sense a family history.”

But to Ms Hall, Stegner’s damned if he do and damned if he don’t. It’s alleged to be underhanded to twist the life story and the writing of a woman to serve your ends, while it’s also held to be wicked to quote her words straight. Stegner/Lyman Ward is quite clear that he is quoting the reminiscences of Susan Burling Ward (who is of course in this role Mary Hallock Foote). Foote’s surviving family had provided permission for him to do this, and he appears to have quoted faithfully though as far as I can discover we haven’t done the work of comparing Hallock Foote’s words with all of Burling Ward’s. Still, there are a lot of parallels in the stories of the two women. The thing lacking from Angle of Repose is any mention of the name Mary Hallock Foote. But while I’m quite inclined to join in the condemnation of Stegner, I have to wonder whether maybe the family didn’t want the name mentioned — in the brief acknowledgment the granddaughter, Janet Micoleau, is referred to as J.M., so it may well be that privacy was requested. Still, some form of words acknowledging that quotation from Ms Foote had taken place would have been “right”. What we have is not, on balance, I think, unambiguously “wrong” though. Perhaps the second sentence of his prefatory notice would have been better if it had read “Though I have quoted many of their words and used many details of their lives and characters . . .”

We won’t ever know the name of “the person from Porlock”, and that person (nor his heirs) is surely not feeling the loss of full attribution for his role in Xanadu. 1971 isn’t perhaps all that long ago, but times have changed. I think we don’t do any good importing our current beliefs into the past and demanding that authors live up to the standards we espouse today. Just read the story, and reflect that things were different back then — in the 1880s and the 1970s.

As it happens I find the book a disappointment on rereading it. I read five novels by Stegner thirty years ago and remember thinking rather highly of them. I dragged my way through Angle of Repose on my second reading though. Is my reaction out of sympathy for all these women he done down? I think not. It’s mainly because I find the book rather boring, and Susan Burling Ward almost intolerably smug, selfish, self-satisfied, and snobbish. (Is it Mr Stegner or Mary Hallock Foote who’s to blame for this I wonder.)

Thanks to Jadviga Villa for the link to the Alta article.

__________________

* The angle of repose as defined in the book by Susan Burling Ward “means the angle at which dirt and pebbles stop rolling”. Lyman, somewhat less scientifically, describes it as “the angle at which a man or woman finally lies down”. In so far as I had thought about the slope of heaps and hills, and beyond our habit at school of sliding/skiing down screes in the Yorkshire fells I had never thought about it, I always imagined it was a pretty constant angle. Not so: I discover at Engineering Toolbox that different materials have different angles of repose. For instance clover seed has an angle of repose of 28% while shredded coconut will take you up to 45%. Garbage only makes it to 30% rather similar to rolled oats. I suspect the metaphoric title has to do with what it took to stop this family fragmenting all the time.

† Now of course winning any prize just means that your book was judged by a panel of “experts” to be better than any other that year. Fiction bestsellers in 1971 and 1972 included Rabbit Redux, The Exorcist, The Day of the Jackal, Jonathan Livingstone Seagull, so perhaps not a vintage year?